There are several similarities Between dementia in cats and humans.

In your house, it might start around 3 a.m.

The cat begins crying in the hallway — loud, long meows, like she’s lost something important. You get up, barefoot on cold tile, and find her blinking in the bathroom doorway.

You refill her food (even though it’s full), rub the soft space between her ears, and sit with her for a while. She settles eventually, but something about it all feels off. Like she’s forgotten where she is.

That confusion? That pacing? That too-late dinner request? It’s not just quirky old-cat behavior. But, it’s eerily familiar if you’ve ever cared for an aging parent or grandparent.

Cats get dementia. It’s called feline cognitive dysfunction syndrome. And it mirrors human Alzheimer’s more closely than you’d expect.

She might cry at night like she’s misplaced something — her bed, the litter box, you. She may drift off mid-morning, then wake up thinking it’s time for breakfast again.

Everything’s still where it was, but it no longer clicks. These are the kinds of patterns we watch for in people, too — disorientation, disrupted sleep, changes in personality. What feels haunting is how familiar it all is.

A few years ago, researchers looked at the brains of 25 elderly cats after they passed away.

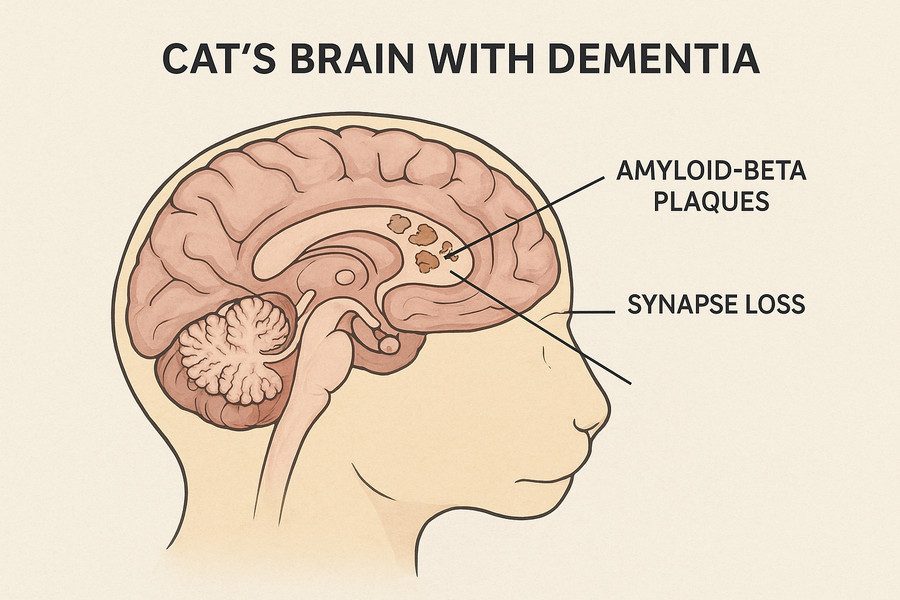

What they found was striking: the same sticky protein that builds up in human Alzheimer’s patients — amyloid-beta — was sitting inside cat synapses.

That’s the place where brain cells talk to each other. And just like in people, when that communication starts breaking down, memory follows.

The brain’s support cells (called microglia and astrocytes) also ramped up. Normally, these little helpers clean things up.

But too much cleanup? It can lead to more loss than protection. And once those synapses are gone, they don’t grow back.

This research came from the University of Edinburgh, but the findings have been echoed in other places, too.

What’s wild is that while mice are often used in Alzheimer’s studies, they don’t naturally get dementia. Cats do.

Which makes them a surprisingly helpful model for understanding how memory fades — and maybe, eventually, how to slow it down.

If you’re sharing your home with an older cat, all of this might feel like too much. Yet, it is also oddly grounding. Because what’s more intimate than aging together?

Here are a few ways to help:

And if her behavior shifts suddenly — confusion, accidents, or pacing, book a vet check. Before assuming it’s memory, check the basics: joints, hormones, and the heart.

They can all play tricks that look the same. Bring a list of what you’ve noticed, maybe even a video. It helps more than you think.

Later that same night, maybe she curls into your side again. The hallway’s quiet. You exhale.

Loving an old cat isn’t flashy or dramatic. It’s quiet work. It means sitting still, showing up, and keeping the light on.

And it matters.

If someone you love is showing signs of memory loss, you don’t have to figure it out alone.

Applewood Our House has spent more than 15 years creating warm, home-style spaces where every resident is known, safe, and cared for with dignity.

Call us today and visit one of our homes to see how we can help your family take the next step with confidence and compassion.